Optimizing a DRF application for I/O bound, AI workloads

DRF is my favourite toolkit for building Web API’s.

However, it has one fatal flaw – it does not support async out of the box. This shouldn’t be a problem for most use cases but if your application I/O heavy (basically every GPT wrapper on the market right now), this can be a significant bottleneck.

What causes this bottleneck?⌗

The GIL prevents more than one thread within a process from executing python bytecode at any given point in time. Which means, while your worker is waiting for a response from an I/O call (api call to Gemini, Anthropic, Openai etc), it just sits there doing nothing. Any other requests assigned to the worker will have to wait until the first request concludes.

There’re a couple of ways to overcome this bottleneck.

For starters, you could try increasing the number of workers used by your application server. So when one of your workers is busy waiting for an I/O call, another worker can handle other requests in the queue.

This is the easiest form of horizontal scaling. However, workers are “process bound”.

A program, (your DRF code) is merely a collection of passive instructions. The active execution of these instructions is called a process.

Processes have an independent memory space, a copy of the python interpreter, a copy of your application’s code, and most importantly their own GIL.

This means you can only have a finite number of processes running on a CPU at any given time, considering the high resource requirement that processes bring. This finite number is not nearly large enough to handle the scale modern web applications operate at.

The number of workers you can spawn on a server is usually 2n + 1, where n is the number of cores on the CPU.

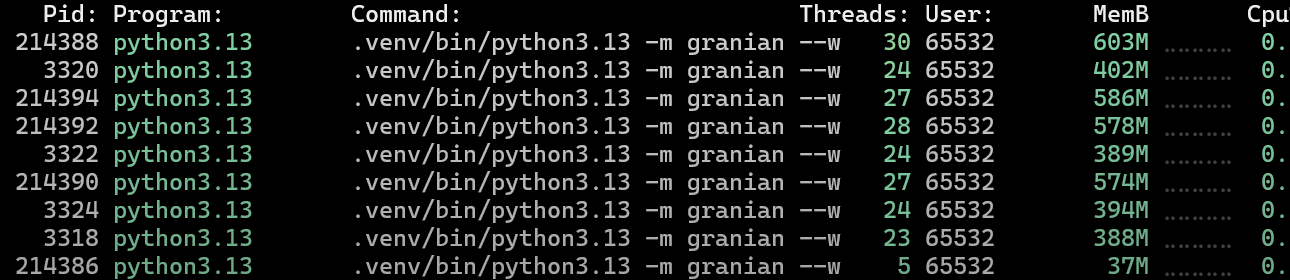

Each pid corresponds to one Granian (an http server similar to gunicorn) worker. Notice how each worker takes up between 400 to 600 mb of memory.

To put things into perspective, an i9-9900K, a 16 core CPU, would be able to host 33 workers at most.

But all of these limitations exist assuming we only have one thread per process. What if we had multiple threads capable of handling multiple requests?

Preemptive multitasking⌗

This is where gunicorn’s gthread worker type comes in.

While thread A waits for a response from a network call, it surrenders the GIL to thread B. This means thread B is now free to handle other requests. Once thread A’s I/O operation concludes, it will fall in line behind any other threads that are waiting to acquire the GIL. Seems like the ideal solution to our problems. WRONG.

Hopping threads is a kernel level operation. This means the OS has to context-switch between user-mode and kernel-mode. The kernel then has to save the context of the old thread and load the entire context of the new thread before making the switch back to user-mode. This is an accurate, safe but slow operation.

So while the gthread worker type ensures that a worker is not entirely handicapped while doing I/O, it comes at the cost of having to constantly switch thread between threads, which is not a cheap operation and relies heavily on the kernel and the os scheduler.

Note that the GIL allows only one thread within a process to execute python bytecode at once, so true multithreading (parallelism) for CPU-intensive tasks isn’t possible in python.

Cooperative multitasking⌗

This is where the gunicorn “gevent” worker type comes in.

gevent “greenlets” are lightweight python objects that can be spawned 100s and thousands of times within a process.

Greenlets work on the principle of “cooperative multitasking”. Which means, a greenlet will continue to work on a request, without interruption, until it hits a blocking I/O call. There’s no external body like the os scheduler or kernel making decisions about when control should be confiscated from one thread and transferred to another.

The OS has absolutely no idea that greenlets exist. A “context-swtich” between greenlets is just a function call within the same process. There’s no transition to kernel mode needed to make this happen.

Then why would one bother using threads at all? While greenlets are incredibly lightweight and dramatically boost your worker’s throughput, there’re no guard rails preventing a greenlet from completely monopolizing the thread it’s running on, and pushing every other greenlet into starvation.

If a thread enters an infinite CPU-bound loop, the OS can forcefully preempt it and allow other threads to run.

There’s no mechanism that enables gevent to do the same.

It relies on the greenlet to voluntarily yield control after hitting a blocking I/O operation, leaving the other greenlets vulnerable to starvation, should the current greenlet hit an infinite CPU bound loop.

What does Gevent under the hood⌗

But how does synchronous code (requests.get(), time.sleep(), etc.) suddenly start behaving cooperatively without you changing a single line? The answer is this goofy technique called monkey-patching.

The default blocking implementations of modules like socket and requests, get modified by gevent to use its cooperative methods at runtime.

Emphasis on “modified” because the entire module doesn’t actually get replaced, just the blocking functions and classes.

When you do

from gevent import monkeymonkey.patch_all()

At the beginning of your wsgi.py file, patch_all() essentially imports all blocking versions of all compatible modules, and modifies them by replacing their blocking implementation with its cooperative ones.

This is a one-time operation that happens before any of your other application code executes. So everytime you import the requests or socket module in your source code, you’ll actually be running the version that has been patched by gevent.

Tldr:

In your wsgi.py file, call the patch_all() method before any of the boilerplate code that you already have. You wsgi.py file should look something like this

from gevent import monkey

monkey.patch_all()

import os

from django.core.wsgi import get_wsgi_application

os.environ.setdefault('DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE', 'myproject.settings')

application = get_wsgi_application()

While deploying your application (im assuming you’re already using a production ready WSGI server)

gunicorn myproject.wsgi:application \

--worker-class gevent \

--workers 4 \

--bind 0.0.0.0:8000

In the next part of this series, I’ll do a benchmark that compares the throughput of a single threaded gunicorn worker vs a gevent one.